Approaches to social change

When movement groups disagree

Have you ever experienced different groups for social change – who seem to share similar values or end goals – criticizing each other? Let’s take the environmental movement as a basic example.

There are people who believe it is each of our responsibility to live sustainably – to eat less meat, to turn off our lightbulbs, and so on – so that we can inspire each other to do so, conserve resources, and bring awareness to environmental issues.

There are others who argue that the environmental and climate issues we face have to be seen and fought systemically – that the fossil fuel industry’s money has corrupted our democracy, and so we have to use everything from lobbying to direct action to correct course.

Then, there are yet others who believe that we can make the most impact by building the future we want to see right now - that we can set up renewable energy systems owned by local communities, hope that new models spread, and, in this way, enact alternatives before we change the whole system.

Now, these people may all share the same values and goals of protecting our resources, our future, and more - but they might still criticize each other! This kind of dynamic obviously is not limited to the environmental movement, and is a constant source of tension within many different movements.

Movement ecology 101

Each of these approaches is based on a different theory of change, or the how and why change is expected to happen.

Sometimes, members of an organization with one theory of change assume other theories of change are inaccurate or inferior. That their approach is the way to change the world.

In reality, every successful movement in history has included groups with multiple approaches to change working in synergy.

The Ayni Institute developed this way of thinking about relationships between groups for social change into a framework called Movement Ecology.

We use the metaphor of “ecology” because, in any natural ecosystem, many different organisms live together in a productive synergy. Each species has its own niche in the environment, and they live in complex relationships with each other (some parasitic, some symbiotic, etc). In a healthy ecosystem, species sustain each other on the whole and diversity flourishes.

In a healthy movement ecosystem, organizations with different theories of change recognize each other's strengths and weaknesses can work together to produce large-scale social change.

Understanding where your organization fits into a movement ecology - and acknowledging your own theory of change explicitly - can help people within your organization be in greater alignment, as well.

3 major theories of change

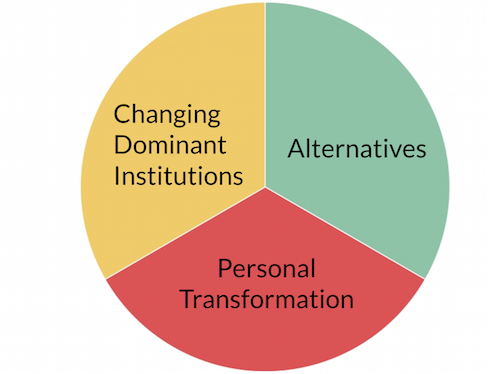

Here are the 3 main theories of change we see at work within a movement ecology. These categories are intentionally simple. One organization may utilize multiple theories of change, but most often, organizations fit dominantly within one slice of the pie.

1. Personal Transformation

This theory of change holds that we must become our best selves as individuals - essentially, so that we can live aligned with the values we claim to espouse and can inspire others to act like we do. Another benefit of personal transformation work, especially leadership or spiritual development, is giving individuals more capacity and energy to serve the community, the movement, or support others. The site of personal transformation is the individual.

2. Alternatives

Alternative institutions and cultures create change by experimenting with alternative ways of doing and being in the world: time banks, worker cooperatives, communes, credit unions, farmer’s markets and monasteries are some examples. All of these push the boundaries of what is possible within our social landscape. Alternative institutions provide the material conditions for us to relate to each other in a way that is aligned with our deepest values. Part of this theory of change is that successful experiments not only foster the wellbeing of those who participate in them, but in some cases they prove the success of innovations and thereby lead the way toward broader changes in law and policy. That said, in the US, alternative institutions are generally private, meaning they tend not to depend on the state (and often occur in spite of it).

3. Changing Dominant Institutions

Those who hold this theory of change believe that by reforming dominant institutions – such as governments and corporations – they can change life more significantly and for more people than by other means. Structure-based organizers and mass protest activists, alongside policy advocates, lobbyists, and lawyers focused on impact litigation, all subscribe to this theory of change.

[PLACEHOLDER FOR TABLE]

Where does Momentum organizing fit in?

The more important questions to ask would be “Where does my own organization fit in? And do we understand our own strengths and weaknesses as one piece of a bigger picture?”

If you’re curious about where organizations that follow a Momentum model would fit in, here’s what Momentum trainers have to say to their participants:

“As a model, Momentum is geared toward those doing dominant institutional reform, but healthy movement ecology includes other actors doing the work of personal transformation and alternative institutions. Healthy movement ecology frees us from the burden to embody every theory of change ourselves; it allows us to honor our unique role in the ecology while being in collaboration and mutualism with others.”