Passive support for Black Lives Matter

Polling on BLM

When it comes to public polling, there are many ways to ask questions about how people perceive racism in the United States – including asking about their direct experiences, where racism ranks among America’s “biggest problems,” whether we need to be making more progress on racial equality, and whether race relations are “generally good” or “generally bad.”

In general, the issue of race relations/racism seems to be a viable field to examine through public polling because there is a long context for polling organizations asking the same questions about it over time – and a political context for the average American to have a formed opinion on it.

It is also an issue that lends itself to relatively binary questions framed in moral terms, as opposed to other issues such as modern day immigration – which often lead to public opinion polling questions framed around a complex and sometimes obscure set of policy options.

Is racism America’s biggest problem?

According to Gallup research, “the percentage of Americans saying race relations/racism is America’s biggest problem has ranged from 0% to 5%.” For example, in November 2014, 1% of the public ranked racism as the top problem. But in December 2014, that share jumped to 13% “on the heels of national protests of police treatment of blacks in the wake of incidents in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, among others.”

Gallup provides the context that concern is “similar to the level found in the midst of the Rodney King case [15%]” in 1992, yet lower than the level of concern [52%] found in 1963 during civil rights era battles.

It is possible to argue that it will be more valuable to see whether the 13% level of concern persists over time during the Movement for Black Lives rather than comparing it to civil rights era concerns since material and political conditions have changed dramatically since then. Detailed answers to this question of America’s biggest problem are not currently publicly available over time through Gallup or other sources.

Trigger events shift public view of race relations – particularly white Americans

According to Pew Research, which used a combination of self-conducted surveys and surveys conducted by CBS and th eNew York Times on the same data, “the public’s view of race relations are more negative now [in 2016] than they have been for much of the 2000s.”

The story of the Movement for Black Lives’ influence on the public’s concern with race relations reveals itself in the following point: between February 2000 and May 2014, more Americans said race relations were “good” than “bad” by double-digit margins.

Pew writes, “By August 2014, after the death of Michael Brown, an unarmed black 18-year-old shot and killed by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri, opinions had changed significantly: 47% described race relations in the U.S. as generally good and 44% as generally bad.”

Delving into answers to this question by demographic breakdown indicate that the events particularly shifted white Americans’ concerns about race relations.

Over the time period between May 2014 to August 2014, during which Michael Brown was killed, the ratio of American answering that race relations were generally “good” versus “bad” went from 55% good / 33% bad to 47% good / 44% bad.

But that change was likely driven by white respondents -- as black respondents showed only a 2% shift on either side of the question, while the percentage of white people saying race relations were “generally bad” went from 27% to 41% in just a few short months. (“Generally good” decreased from 60% to 49% among white people, too.)

For reference, in May 1992, after the Rodney King riots in Los Angeles, 25% of Americans answered that race relations were “generally good” and 68% rated the situation as “generally bad” – including 67% of white respondents.

After the murder of Michael Brown, white respondents were still at 41% responding “generally bad,” but less than a year later concern grew even more pronounced after the death of Freddie Gray in Baltimore in May 2015.

In May 2015, 34% of all Americans were at “generally good” and 61% were at “generally bad” – and 62% of white Americans showed concern at “generally bad” as well. This is a 35% increase in white Americans rating race relations at “generally bad” in one year and a 21% increase since the last major “trigger event” (Michael Brown’s death and Ferguson protests 9 months earlier.

AKA, after the death of Freddie Gray, Americans and white Americans were reaching to concerns about race relations close to the level shown in 1992, for the first time in over two decades.

Concern lowered (but remained a net negative, with more rating “bad” than “good”) going into May 2016. Data is not yet available past May 2016.

It is worth noting that the question of whether race relations are “generally good” or “generally bad” can contain a variety of opinions about the problem more specifically, including who is to blame and how to move forward.

Visual representation from Pew:

Continued: Newest data on racial attitudes in 2017

As recently as October 2017, Pew Research released the results of more polling on racial attitudes that was conducted in June and July 2017.

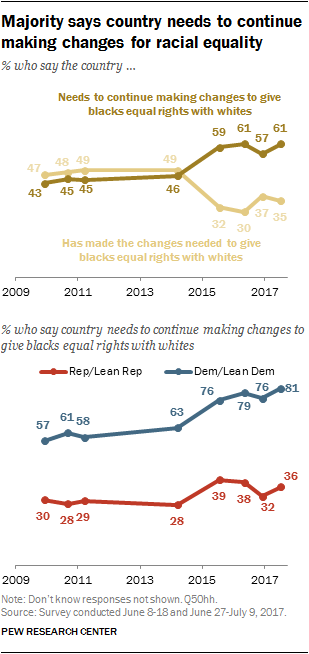

There is a dramatic growth of Americans who believe our country still "needs to continue making changes to give blacks equal rights with whites" – a shift from 46% in 2014 to 61% in 2017. In 2014, 49% of Americans believed we had already "made the changes needed to give blacks equal rights with whites," and only 35% of respondents opted for that choice in 2017. As Pew puts it, "The current balance of opinion has changed little over the past few years but marks a shift from 2014 and earlier when the public was more evenly divided on this question."

Let's say that again: there's been a 15-point jump in white people who say we need to make more progress giving black people equal rights in just 3 years, from 2014 to 2017. To belabor the point, the Black Lives Matter movement officially began in 2013.

See graphs below, including a graph showing the partisan breakdown of those responding that we still have more changes to make:

Click through to Pew for more statistics and graphs showing that the share of Hispanic and white respondents responding that more needs to be done is growing.

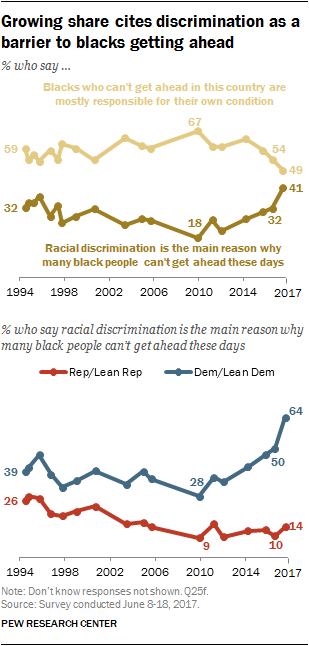

There is also a shift in the perception of racial discrimination as a reason "why many black people can't get ahead these days" – the respondents agreeing with racial discrimination as the primary reason is at 41% in 2017, 9 points higher than just last year and the highest level recorded since 1994:

As the graph above shows, "This shift in overall attitudes about whether discrimination inhibits the progress of blacks in the country is almost entirely the result of changing views among Democrats. Republican views have moved only modestly. As a result, the already wide partisan gap on this question has grown considerably larger over the course of recent years" (Pew).

A key point to pull out – as recently as 2014, fewer than half (41%) of Democrats cited discrimination as the biggest barrier to black Americans. Now, 64% are responding that it is.

Note: the above results were from polling conducted before the events in Charlottesville, Virginia of August 2017.

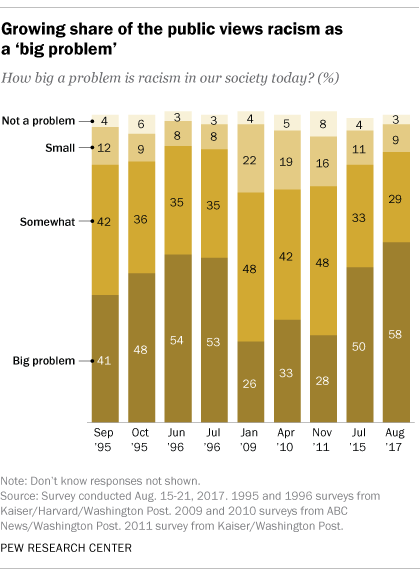

Pew also posted results from a survey about racial attitudes conducted from August 15 - 21, 2017, shortly after the violence in Charlottesville – asking how many Americans view racism as a 'big problem.' (Note: this is different than the data discussed above in Is racism America’s biggest problem? which was formulated through a different question).

As you can see, the amount of respondents saying that racism is a 'big problem' has been increasing since 2001 and has jumped 8 points in just two years from 50% in 2015 to 58% in 2017. Again: in 2011, less than half of Americans saw racism as a 'big problem' in the United States – significantly less than half, at 28%. The Black Lives Matter movement came along in 2013.

Pew has an interesting note on the partisan gap in considering racism a 'big problem':

Since 2009, the first year of Barack Obama’s presidency, growing numbers of both Democrats and Republicans have seen racism as a big problem. In 2015, 58% of Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents and 40% of Republicans and Republican leaners said racism was a major problem, up from 32% and 18%, respectively, in 2009.

Since then, however, the share of Democrats expressing this view has climbed 18 percentage points – from 58% to 76% – while the share of Republicans saying this held relatively stable. Today, 37% of Republicans view racism as a big problem; 40% did so in 2015.

It would be interesting to explore more factors that may be causing evolving views on racism to be more of a partisan issue since 2015, specifically– and one may start by thinking about the beginning of the 2016 election cycle and the dogwhistle politics adopted by the Trump campaign in reference to movements for racial justice like BLM.

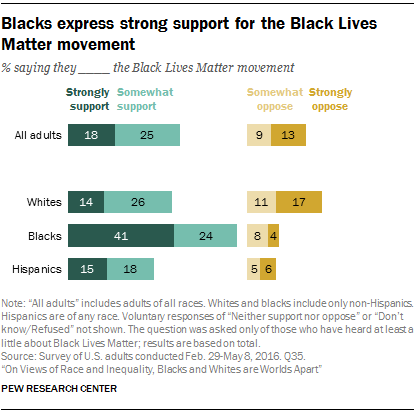

Polling on attitudes towards Black Lives Matter movement

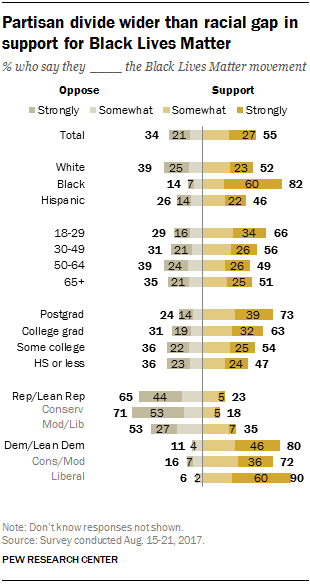

At time of writing, Pew has two reports that ask questions about support for the Black Lives Matter movement by demographic category: a report showing survey results from February - May 2016, and a report showing survey results from August 2017.

First, here is a summary table we put together from available Pew data on total respondents' support or opposition to BLM (amount of detail reflects available detail in data provided by Pew):

| Feb - May 2016 | August 2017 |

|---|---|

| 43% somewhat or strongly support BLM (25% somewhat, 18% strongly). | 55% somewhat or strongly support BLM. |

| 22% somewhat or strongly oppose the movement (9% somewhat, 13% strongly). | 34% oppose the movement. |

Key point:

Total support for BLM went up by 12% in just over a year, and total opposition to BLM went up by 12%, as well. This suggests there would likely be a smaller category of respondents who remain 'neutral' (I don't know/I'm not sure). This is in line with Momentum ideas of polarization; that as a movement gains strength, it forces people to choose a moral stance and the opposition may very well grow, as well.

Second, here is a summary table we made from the available Pew data on differences between white and black support for BLM (blank spaces represent points not published by Pew):

| February - May 2016 | August 2017 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Somewhat support | Strongly support | Total support | Somewhat support | Strongly support | Total support | |

| Whites | 26% | 14% | 40% | 29% | 23% | 52% |

| Blacks | ? | 41% | ? | 22% | 60% | 82% |

Key point:

From spring 2016 to summer 2017, the % of whites who "strongly support" the Black Lives Matter movement went up by 9 points. The % of blacks who "strongly support" BLM went up by 19%.

See more data from the 2016 survey:

And see more data from the 2017 survey:

Material evidence that movement work is causing the shift

A July 2015 Gallup poll found that black Americans were no more likely to report having been mistreated by the police than they were in 2013 or in previous surveys, dating back to 1997. Other sources have supported the suggestion that incidents of police violence have not been increasing in recent years, and that more attention is being paid to the injustices being committed.

Mic writer Zeeshan Aleem points out:

“There is no national database that systematically chronicles reports of police violence against citizens, let alone one that detects patterns in violence associated with race. But the limited data that does exist suggests that there has not been an exceptional increase in police homicides, and some criminologists say that they are at the lowest they’ve been in recent memory. [...] Thus it’s likely that shifts in the national perception of race relations has been shaped by the salience of the Black Lives Matter movement, fueled by the proliferation of cellphones videos and social media. Constant protests, die-ins, community gatherings, online organizing, occasional riots and real-life confrontation with politicians have had a very real impact on the country's understanding of race.”

Social Media Coverage

Wesley Lowery wrote in The Guardian in January 2017:

“As of March 2016, the 10th anniversary of Twitter, the hashtag #blacklivesmatter had been used more than 12m times – the third most of any hashtag related to a social cause. At the top of the list, however, sits #Ferguson, the most-used hashtag promoting a social cause in the history of Twitter, tweeted more than 27m times.

The Pew Research Center sums up the development of the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag on Twitter:

“The phrase “black lives matter” was first used by a black community organizer in a Facebook post following the July 2013 acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting death of black 17-year-old Trayvon Martin. Despite its widespread presence today, the hashtag was slow to gain prominence: during the second half of 2013, it appeared on Twitter a total of just 5,106 times (or about 30 times a day).

Both the use of the hashtag and the influence of the broader Black Lives Matter movement accelerated greatly in August 2014 when Michael Brown, a black teenager, was fatally shot by a white police officer in Ferguson, Missouri.

The #BlackLivesMatter hashtag appeared an average of 58,747 times per day in the roughly three weeks following Brown’s death. However, the use of the hashtag increased dramatically three months later when on November 25, the day after a Ferguson grand jury decided not to indict the officer involved in Brown’s death, the #BlackLivesMatter hashtag appeared 172,772 times. During the subsequent three weeks, the hashtag was used 1.7 million times.

Since late 2014, #BlackLivesMatter has been a continuous presence on Twitter, but its use has increased around some specific events.”

A report called Beyond the Hashtags looked at hashtag usage associated with #BlackLivesMatter from June 2014 to May 2015 (page 21):

The following is the key observation about this hashtag spread:

“As Table 3 shows, some keywords were considerably more popular than others. #Ferguson was by far the most-mentioned, appearing in more than half of all tweets. Michael Brown was mentioned more than any other victim, followed by Eric Garner, Freddie Gray, and Walter Scott. Few clear patterns emerge among those who are widely and seldom discussed—at both the high and low ends there are cases that span a wide range of ages, locations, and dates, with and without accompanying video evidence.One exception to this general rule is that the four deaths that occurred prior to Eric Garner’s yield very little Twitter conversation.

This suggests that while social media may have played a critical role in helping activists push police violence to the forefront of public consciousness, this was by no means an automatic process.The mere presence of articles about police killings on social media was not enough: a critical mass of concerned parties had to decide to aggregate their anger into a movement.”

See another tweet analysis from Beyond the Hashtags (p22):

Beyond the Hashtags analysis:

“As with most issues, attention to police violence on Twitter is episodic. Figure 4 shows that comparatively few people were engaged with the issue prior to Michael Brown’s killing on August 9. The sustained attention spike that extends from that date through the end of the month encompasses the iconic initial Ferguson protests. After that, tweet volume plummets precipitously, rarely exceeding 100,000 tweets per day until the non-indictments of Michael Brown’s and Eric Garner’s killers (on November 24 and December 3, respectively). The former event yielded the time frame’s highest total number of tweets on a single day—3,420,934. After the two non-indictments, the daily tweet count never again crosses one million, though there are several smaller spikes on April 8 (the day Walter Scott was killed in North Charleston, SC), April 28, and May 1 (both during the Freddie Gray protests in Baltimore).”

Interviewed by USA Today in August 2016, Deen Freelon, one of the authors of the _Beyond the Hashtag _report said the following:

“The lack of an indictment against Wilson, Freelon notes, was the tipping point. Twitter activity around the movement never fell to its former levels and a higher baseline emerged."

“What really bolstered the movement, Freelon said, were the protests and police response in the days after the Ferguson incident. By Aug. 12, activists hit the streets. Police responded with armored vehicles, military-grade equipment and what critics considered disproportionate force. Images spread online of officers firing tear gas and rubber bullets at crowds. ‘We saw no examples of highly-retweeted eyewitness accounts supporting the police response,’ the study concluded.”

Pew has also compared usage of #BlackLivesMatter to #AllLivesMatter, finding the former was used 8 times as often as the latter:

Pew additionally found that the tag was more frequently used in supportive tweets about the movement than in neutral or critical tweets:

Another zoomed-in example of how the hashtag has spiked in usage after certain trigger events, by the New York Times (2015):

Pew also shows that general mentions of race/race-related topics spikes after news events:

Media Coverage

Measuring media coverage of the Black Lives Matter movement in comparison to past movements for justice comes with an assumption. The proliferation of self-publication tools such as cell phone cameras and platforms such as Twitter and Facebook has made the possibility for citizens to spread their direct accounts of police discrimination or police brutality exponentially larger – with less gatekeepers deciding whether a story is worth covering, and with virality often determined by the perceived injustice/violence of the situation. Graph from 538:

Television coverage vs. social media activity

We decided to compare some of the Twitter activity documented in _Beyond the Hashtags _with mentions of terms from "police brutality" to "Black Lives Matter" on television news networks as found in the dataset of GDELT's Television News Explorer.

Trigger events are essentially movement moments that capture an unusual amount of attention and draw unusual amounts of participation from the public. So, looking at the Twitter spikes in _Beyond the Hashtags _may lead us to think that the events that provoked Twitter spikes are _the _trigger events. Yet, below, we see that sometimes events may cause spikes in Twitter mentions but not national TV network mentions – or vice-versa.

What kind of 'attention metric' defines a trigger event as having more impact than another? Why do certain events get more traction on television vs. Twitter? Do different media platforms' responses represent the possibility that the same event may be a trigger for different kinds of audiences (i.e., people who watch cable news vs people who are on Twitter)?

Social scientists are already invested in exploring the differences in how people interact with and on new media platforms like Twitter and more traditional media platforms like cable news.

We present these graphs below as food for thought for those researchers and for movement organizers and funders looking to understand how we can assess trigger events in more detail.

Comparison #1:

The same trigger events come through but with different relative importance – Twitter put more energy into the non-indictment of Darren Wilson, while TV focused on the death of Freddie Gray and (likely) subsequent protests and riots in Baltimore. BLM shutting down the Mall of America came through as a trigger event on TV that did not make as much of a splash on Twitter.

Comparison #2:

Note: it's worth remembering that the Beyond the Hashtags _Tweet snapshot in the top corner is constructed off of not only tweets with the #BlackLivesMatter tag but also tweets with dozens of associated keywords. _Beyond the Hashtags analysis, Pew Research, and the _New York Times _graphs above all confirm that #BlackLivesMatter as a tag first appeared on Twitter in 2013, picked up more usage after Michael Brown was killed in August 2014, but really only first skyrocketed after the non-indictment of Darren Wilson in November 2014. In conversation with organizer and Momentum trainer James Hayes, he confirmed that "Black Lives Matter" did not become synonymous with the movement coming out of Ferguson, MO, until that winter 2014 period.

On comparison #2 - TV did not start saying “Black Lives Matter” until the non-indictment of Darren Wilson specifically. Compared to the previous graph, it seems like TV did cover the death of Michael Brown and protests there (in Period 3, which is almost flat here) but may have talked about it in terms like “police brutality” without referring to the movement by name until somewhat later.

Comparison #3:

Again in conversation with OH organizer and Momentum trainer James Hayes, Hayes saw this graph of television discussing the events in Ferguson in terms of "racism"/"police" earlier than they started saying "Black Lives Matter" as confirmation that the "movement was getting its point across but that it's meta-branding wasn't solidified" at that point.

Hayes brought up an example of organizing with the Ohio Student Association after John Crawford III was killed by a police officer at a Wal-mart in Ohio. OSA, co-founded by Hayes, was running a campaign specifically to pressure the store and authorities to release surveillance footage with the hashtags #ReleaseTheTapes and #BlackLivesMatter. Hayes said the local newspaper was referring to the organizing efforts as "the Release the Tapes movement." This was in August/September 2014.

Hayes said that when it came to December 2015, many more black organizing efforts get automatically labeled under 'Black Lives Matter' by the media and by the public, which has both pros and cons in regards to distribution of attention, power, and resources for different organizing groups.

Comparison #4:

This is an interesting comparison because Beyond the Hashtags _noted that November 24, the day the non-indictment of Darren Wilson was announced, was the day of highest-ever Tweet volume in their dataset followed by a lower peak for the Pantaleo non-indictment on December 3rd (Daniel Pantaleo is a police officer who shot and killed Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York). TV news network mentions of both "police brutality" and "Black Lives Matter" seem low around the time of the first non-indictment and pick up more use around the second non-indictment. Also worth noting that the scales of the graphs are different – there were actually more mentions of "Black Lives Matter" than "police brutality" around December 3rd and similar levels of both towards December 13 or so. This is interesting because the graphs seem to show around December 1st, before Pantaleo's non-indictment, there were more mentions of police brutality and almost none of "Black Lives Matter." This seems to point to the time of Pantaleo's non-indictment as _the _point when "Black Lives Matter" broke through into more common usage on television news. It would be great to have more research on television coverage of Black Lives Matter akin to the _Beyond the Hashtags analysis of BLM on Twitter.

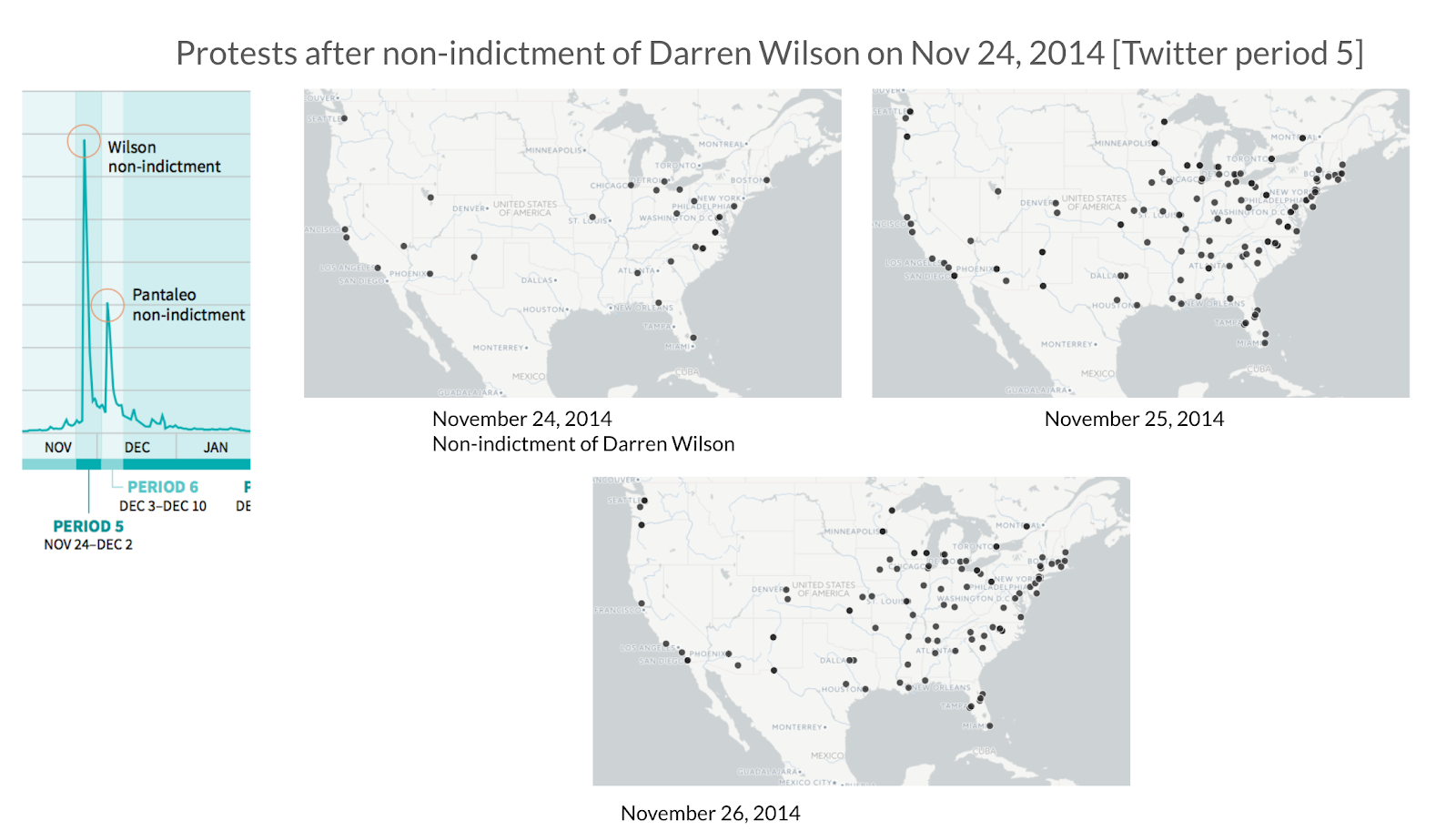

Social media activity vs. protest activity

Note: these maps of protest activity compared to _Beyond the Hashtags _Twitter snapshots are from the amazing website Elephrame, created by Alisa Robinson, which catalogues ideas and data including records of Black Lives Matter-related protests. Please explore Elephrame for more; it was the only existing attempt to catalogue all BLM protests that we could find.

Comparison #1:

This is a note to say that when we look at trigger events from the perspective of which events register media attention – it is important not to assume that a trigger event always means a large number of protests or a large protest or anything else specific. Different sizes and kinds of protests can be trigger events and have different meaning for varying media platforms. The one dot on the protest map on August 10, 2014, represents the first protest organized after the death of Michael Brown. August 14 was the largest day of nationally-distributed protests since his death. And August 18 was a high media-coverage day, presumably because Governor Nixon called the National Guard on Ferguson, MO, protesters. That corresponds to the second peak in Period 3 of the Twitter snapshot above.

Comparison #2:

Continuing from the commentary in Comparison #1 above, the two bottom maps are examples of protests significant in size that did not have peaks on Twitter like other days of protest did. Depending on how we define trigger events, lacking a certain type of media or social media attention may mean that a protest was not a trigger event – just a protest significant in other ways.

Comparison #3:

Just an example of the national spread of protests in the few days after the announcement of Darren Wilson's non-indictment - which also happened to be the day of highest Tweet volume recorded in the Beyond the Hashtags dataset.

Comparison #5:

Compared to the above graphs, there appear to be less nationally-distributed protests right after the non-indictment of Daniel Pantaleo than after the non-indictment of Darren Wilson. However, there were major protests on December 4 & December 5 of 10,000+ people in New York City (Pantaleo killed Eric Garner in Staten Island, New York).

OH organizer and Momentum trainer James Hayes said there was more organizing infrastructure in and more attention focused on Ferguson, MO, and that time, and more preparation from organizers on the ground there to support national actions related to the non-indictment of Darren Wilson. Hayes said Ferguson was also acting as more of a symbol of what black people have been through in this country historically than New York could. Hayes also pointed out that the nature of media coverage will mean some actions don't get listed even in the most thorough database there is; for example, he was participating in a "die-in" protest on the Las Vegas strip at that time which is not included in the Elephrame database.

Conclusion

Once more, these graphs comparing Twitter activity and television network news coverage based on certain terms or reports of protests are meant to be food for thought and show some of the complexities of assessing trigger events.

In sum, knowing how a protest drew more passive support and active support – including media coverage, social media activity, and protest activity – can hint that that event can be considered as a potential trigger event. Really, trigger events are identified in retrospect when they already have created the space that led to a concrete win of the movement's demands.