Additional criminal justice research

As part of our research process, we looked for indicators of public opinion on a variety of criminal justice measures and looked for examples of campaigns that seemed to be driven by Momentum organizing ideas.

Part of the winding road we took in researching the contemporary movement for racial justice is understanding that the fields of "racial justice" and "criminal justice" are complex, overlapping and interrelated, and yet distinct in the public consciousness. That distinction can be seen in how the Black Lives Matter movement is mostly perceived as focusing on racialized policing and police violence towards communities of color – which is, of course, connected to an end result of racialized incarceration. For example, Black Lives Matter messaging has so far focused more on police violence than it has on the death penalty.

A lot of the more "criminal justice"-focused research (i.e., perceptions of incarceration, sentencing, death penalty etc.) was not included in our 'final' selections for explaining measures of active and passive support for the Black Lives Matter movement, but we would like to share it here in case it could be an interesting starting point for others.

- General resources for studying public opinion on criminal justice

- Polling on the death penalty

- Polling on incarceration overall, drug crime sentencing reform, mandatory minimums

- A note on the Close Rikers campaign

General resources for studying public opinion on criminal justice

A few good resources we found for statistics on how the public thinks about criminal justice reform - see specific poll citations below:

- Gallup News articles, including section on Crime & Personal Safety

- Pew Research, topic category: Criminal Justice

- Public opinion resources by the Prison Policy Initiative

- Report by the Alliance for Safety and Justice on crime victims' views of criminal justice reform

- Great overview report by The Opportunity Project on public opinion of all sorts of CJ reform issues & media coverage

Polling on the death penalty

Gallup summarized support for the death penalty in 2015:

About six in 10 Americans favor the use of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder, similar to 2014. This continues a gradual decline in support for the procedure since reaching its all-time high point of 80% in 1994....These results come from Gallup's annual Crime poll, conducted Oct. 7-11, 2015. While the public has, with one exception, favored the death penalty over the 78 years Gallup has asked this question, support for the measure has varied considerably. The low point for support, 42%, came in the 1960s, with support reaching its peak in the mid-1990s and generally declining since that point. Over the past decade, however, there has been minimal fluctuation in the percentage of adults who favor the death penalty, with support always at or above 60%.

In 2016 poll results, Gallup added another data point – that support had dropped to 60%:

As voters in several states prepare to vote on death penalty initiatives, 60% of Americans say they are in favor of the death penalty for persons convicted of murder. This figure is similar to the 61% average since 2011 but down from 66% support between 2000 and 2010 and the all-time high of 80% in 1994. Support for the death penalty has not been lower since it was 57% in November 1972.

An interesting breadcrumb of information for that drop in support is that "The recent decline in U.S. support for the death penalty is mostly attributable to a decline in the percentage of Democrats favoring the practice." This does suggest that the "common sense" about crime and punishment on the left/liberal side may be changing and that would be a good area to look for signs of movement activity influence.

Another Gallup historical overview shows detailed tables of polling over the years on the death penalty. Questions include:

- "Are you in favor of the death penalty for a person convicted of murder?" (1937 - 2016)

- "In your opinion, is the death penalty imposed -- [ROTATED: too often, about the right amount, or not often enough]?" (2001 - 2016)

- "Generally speaking, do you believe the death penalty is applied fairly or unfairly in this country today?" (2000-2016)

For all three of those questions, beginning and end results are relatively similar with fluctuations over the years. Significance of the (relatively small) fluctuations should be analyzed with more statistical rigor, but one interesting start point seems to be that for the question about whether the death penalty is imposed "too often," it looks like "too often" values have been in the higher range and "not enough" in the lower range since 2011.

Gallup explains that the relatively consistent majority of Americans who support the death penalty does not compeletely reflect that the death penalty is actually becoming less common:

This reliably high majority of support belies a powerful current of change in recent years that has rendered the death penalty a far rarer judicial outcome than before. In May, Nebraska became the 19th state (along with D.C.) to ban the death penalty, and the seventh state since 2007. Meanwhile, the number of death sentences issued in 2014 was the lowest since the reinstatement of the punishment in 1976, and the number of executions carried out in 2014 was one of the lowest on record.

Finally, Gallup also explains in the same piece that opinions are polarized by race:

A large gulf exists between whites and blacks in their support for the death penalty. In a combined 2014-2015 sample, 68% of whites said they were in favor of the death penalty, while 29% were opposed. Blacks tilt almost as heavily in the opposite direction -- 55% oppose the death penalty, compared with 39% in favor. This pattern is in alignment with previous Gallup findings, including in 2007. The opposition among blacks may be related to the disparity between blacks making up 42% of the current death row population but just 13% of the overall U.S. population.

Check out additional survey results with slightly different numbers but a similar sentiment – that support for the death penalty remains in the majority but is decreasing, mostly with decline in Democrats supporting it – from Pew Research in 2015.

Relevance for Momentum research:

This is an interesting phenomenon. Public opinion in support of the death penalty seems to be dropping (see 2016 results), but it still shows a majority of Americans in favor. Yet, a current of judicial change is moving to make the death penalty more rare across the country. So, we decided that (the movement against) the death penalty at this moment is not a strong example of a Momentum-style campaign.

As mentioned above, an interesting starting point for looking at movement influence would be to explore the data point that "The recent decline in U.S. support for the death penalty is mostly attributable to a decline in the percentage of Democrats favoring the practice." (Gallup 2016)

Questions for exploring this further through a Momentum perspective:

- What is the relationship, if any, between public opinion and judicial moves against the death penalty in localized areas (such as states) where it is banned? These polls we have been reading about are national.

- In some cases, judicial decisions can be followed by shifts in public opinion. Is this happening with bans on the death penalty? Can those shifts in public opinion catalyze more grassroots organizing on related issues?

- What are the trigger events that cause the shifts in the polling data from year to year?

- What is causing Democrats to reduce their support for the death penalty faster than Republicans?

Polling on incarceration overall, drug crime sentencing reform, mandatory minimums

Gallup research in 2016 showed that Americans' views are shifting on the toughness of the criminal justice system:

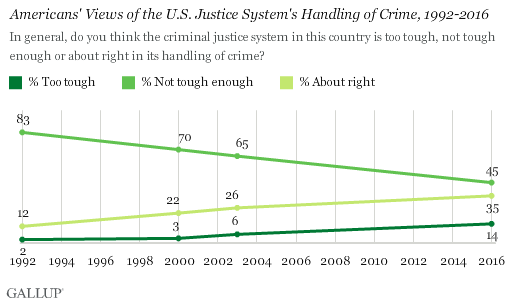

Americans' views of how the criminal justice system is handling crime have shifted considerably over the past decade. Currently, 45% say the justice system is "not tough enough" – down from 65% in 2003 and even higher majorities before then. Americans are now more likely than they have been in three prior polls to describe the justice system's approach as "about right" (35%) or "too tough" (14%).

As expected, Gallup reports that Democrats are more likely than Republicans to answer "too tough," and non-white respondents are more likely than white respondents to do the same.

One interesting point is that between 2000 and 2016, white respondents seem to have a large decrease in % of those who respond "not tough enough" and a small increase in those responding "too tough:"

From left "too tough," "not tough enough," and "about right:"President of the Alliance for Safety and Justice Lenore Anderson did say that she believes there has been a massive shift in common sense about race, crime, and punishment even since 2005 – much of it driven by Michelle Alexander's book The New Jim Crow (2010) and the Black Lives Matter movement (2013 - ongoing).

Separately, the ACLU commissioned a survey in 2015, administered by the Benenson Strategy Group, that found majorities of Americans across political parties reporting that prison populations should be decreased:

- Republicans and Democrats alike say that communities will be safer when the criminal justice system reduces the number of people behind bars and increases the treatment of mental illness and addiction, which are seen as primary root causes of crime.

- Overall, 69% of voters say it is important for the country to reduce its prison populations, including 81% of Democrats, 71% of Independents and 54% of Republicans.

- In a sharp shift away from the 1980s and 1990s, when incarceration was seen as a tool to reduce crime, voters now believe by two-to-one that reducing the prison population will make communities safer by facilitating more investments in crime prevention and rehabilitation strategies.

Gallup also points to responses indicating that drug crime sentencing may be an opportunity to push for bipartisan reform:

U.S. adults are much more likely, however, to describe drug crime sentencing guidelines as "too tough" compared with their opinions of the system's handling of overall crime, and this is the case among both racial and political party groups.

In 2016, there was some Congressional progress on a drug sentencing reform act that has since stalled, and President Obama commuted sentences for 58 individuals convicted of drug-related crimes. It seems that 2016 is the first year that Gallup has asked a survey question about whether drug crime sentencing guidelines are too tough – in itself, the kind of questions that a polling group asks are reflective of a certain level of societal concern.

An additional report by Pew Research from 2014 shows a substantial shift in public support between 2001 and 2014 for governments shifting away from mandatory prison terms for non-violent drug crimes:

Some digging into the research showed that Pew only had answers to this question in 2001 and 2014, not intervening years (unless they have data that is not publicly available).

This is supported by yet another polling report conducted by another organization for the Pew Charitable Trusts in 2016, which found high support for ending mandatory minimum sentencing for drug crimes and all crimes:

Relevance for Momentum research:

There are two main movement breadcrumbs here – one, that white people's perceptions of how "tough" the criminal justice system is may point to some movement influence, and two, that the shifting public opinion on drug crime sentencing can point to an opening for further movement activity on that issue.

Questions for exploring this further through a Momentum perspective:

- The Black Lives Matter movement's most visible protests have often had a focus on racialized policing and police violence against communities of color. How might we measure whether the BLM movement as a whole is also inciting people to reconsider their views on the criminal justice system (particularly incarceration)?

- Are there any groups employing movement strategies to specifically work towards drug crime sentencing reform as a goal? (Our initial research did not turn up much.)

A note on the Close Rikers campaign

In another page, we chose to cover the #ByeAnita campaign to unseat state's attorney Anita Alvarez in Chicago as an example of how a campaign won a specific reform/electoral goal by benefiting from Momentum-type mobilization and shifting of the "common sense" (through the broader Black Lives Matter movement).

In our research process, we considered other campaigns to use as that example and one that we almost used was the campaign to close the Rikers Island Jail Complex in New York City.

The #CLOSErikers campaign, led by JustLeadershipUSA under the leadership of Glenn E. Martin, was launched in April 2016. Coverage from The Observer:

“There have been attempts to force the closure of the Rikers Island jail for years, but Glenn Martin thinks that the failed efforts so far have been missing a key ingredient: ‘the community’s voice.’ That’s why Mr. Martin, the founder of JustLeadershipUSA (JLUSA) has put together #, a group formed by 58 community, faith-based, and criminal justice reform organizations, which launched its campaign with a rally on the steps of City Hall yesterday.”

In March 2017, the campaign scored a major victory when Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that he would work on formulating a plan to shut Rikers over the next 10 years. At time of writing, activists are continuing to push the mayor to accelerate and implement that process.

There were several other significant pushes to close Rikers Island – the site of much abuse and violence including the tragic story of Kalief Browder's unjust incarceration without trial and subsequent suicide. Previous discussions and campaigns about closing Rikers crystallized in the 1970s under Mayor Koch and in the 2000s under Mayor Bloomberg.

Herbert Sturtz was working on the Rikers issue under the Koch administration and then was also part of the independent commission that finally made the recommendation to close it under de Blasio. He credits Browder's story with 'humanizing' the story about why Rikers Island should be closed and re-opening political space for that decision to come through.

Our initial research and conversations with consultants suggested that there were other factors at play that were more significant to closing Rikers than the influence of the Black Lives Matter movement – so we chose the #ByeAnita campaign to expand as our case study, because it made clear use of the "new common sense" on race and police violence made clear by BLM. However, there is a lot of room for further research on this question – did Black Lives Matter contribute to making a demand, that had failed at least twice before, successful in 2017?